Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature currently requires accessing the site using the built-in Safari browser.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Blast from the past

- Thread starter Administrator

- Start date

On March 27, 1977, two Boeing 747 passenger jets, operating KLM Flight 4805 and Pan Am Flight 1736, collided on the runway at Los Rodeos Airport (now Tenerife North Airport) on the Spanish island of Tenerife. Resulting in 583 fatalities, the Tenerife airport disaster is the deadliest accident in aviation history.

A terrorist incident at Gran Canaria Airport had caused many flights to be diverted to Los Rodeos, including the two aircraft involved in the accident. The airport quickly became congested with parked airplanes blocking the only taxiway and forcing departing aircraft to taxi on the runway instead. Patches of thick fog were drifting across the airfield; hence visibility was greatly reduced for pilots and the control tower.

Immediately after lining up with the runway, the KLM pilot advanced the throttles and the aircraft started to move forward. The co-pilot advised the captain that ATC clearance had not yet been given, and Captain Veldhuyzen van Zanten responded, ?I know that. Go ahead, ask.? Meurs then radioed the tower that they were ?ready for takeoff? and ?waiting for our ATC clearance.? The KLM crew then received instructions which specified the route that the aircraft was to follow after takeoff. The instructions used the word ?takeoff,? but did not include an explicit statement that they were cleared for takeoff.

Meurs read the flight clearance back to the controller, completing the readback with the statement: ?We are now at takeoff.? Captain Veldhuyzen van Zanten interrupted the co-pilot?s read-back with the comment, ?We?re going.?

The controller, who could not see the runway due to the fog, initially responded with ?OK? (terminology which is nonstandard), which reinforced the KLM captain?s misinterpretation that they had takeoff clearance. The controller?s response of ?OK? to the co-pilot?s nonstandard statement that they were ?now at takeoff? was likely due to his misinterpretation that they were in takeoff position and ready to begin the roll when takeoff clearance was received, but not in the process of taking off. The controller then immediately added ?stand by for takeoff, I will call you,? indicating that he had not intended the clearance to be interpreted as a takeoff clearance.

A simultaneous radio call from the Pan Am crew caused mutual interference on the radio frequency, which was audible in the KLM cockpit as a three-second-long whistling sound (or heterodyne). This caused the KLM crew to miss the crucial latter portion of the tower?s response. The Pan Am crew?s transmission was ?We?re still taxiing down the runway, the Clipper 1736!? This message was also blocked by the interference and inaudible to the KLM crew. Either message, if heard in the KLM cockpit, would have alerted the crew to the situation and given them time to abort the takeoff attempt.

Due to the fog, neither crew was able to see the other plane on the runway ahead of them. In addition, neither of the aircraft could be seen from the control tower, and the airport was not equipped with ground radar.

After the KLM plane had started its takeoff roll, the tower instructed the Pan Am crew to ?report when runway clear.? The Pan Am crew replied: ?OK, we?ll report when we?re clear.? On hearing this, the KLM flight engineer expressed his concern about the Pan Am not being clear of the runway by asking the pilots in his own cockpit, ?Is he not clear, that Pan American?? Veldhuyzen van Zanten emphatically replied ?Oh, yes!? and continued with the takeoff.

Moments later, the Pan Am crew spotted the KLM?s landing lights through the fog. When it became clear that the KLM was approaching at takeoff speed, Grubbs exclaimed, ?Goddamn, that son-of-a-bitch is coming straight at us!? while the co-pilot Robert Bragg yelled, ?Get off! Get off! Get off!?. The Pan Am crew applied full power to the throttles and took a sharp left turn towards the grass in an attempt to avoid a collision. By the time the KLM pilots saw the Pan Am, they were already traveling too fast to stop. In desperation the pilots prematurely rotated the aircraft and attempted to clear the Pan Am by climbing away. The KLM was within 330 ft of the Pan Am when it left the ground. Its nose gear cleared the Pan Am, but the engines, lower fuselage and main landing gear struck the upper right side of the Pan Am?s fuselage at approximately 140 knots.

Both airplanes were destroyed. All 234 passengers and 14 crew members in the KLM plane died, as did 326 passengers and nine crew members aboard the Pan Am, primarily due to the fire and explosions resulting from the fuel spilled and ignited in the impact. The other 54 passengers and seven crew members aboard the Pan Am aircraft survived, including the captain, first officer and flight engineer.

The subsequent investigation by Spanish authorities concluded that the primary cause of the accident was the KLM captain?s decision to take off in the mistaken belief that a takeoff clearance from air traffic control (ATC) had been issued. Dutch investigators placed a greater emphasis on a mutual misunderstanding in radio communications between the KLM crew and ATC, but ultimately KLM admitted that their crew was responsible for the accident and the airline agreed to financially compensate the relatives of all of the victims.

The disaster had a lasting influence on the industry, highlighting in particular the vital importance of using standardized phraseology in radio communications. Cockpit procedures were also reviewed, contributing to the establishment of crew resource management as a fundamental part of airline pilots? training.

A terrorist incident at Gran Canaria Airport had caused many flights to be diverted to Los Rodeos, including the two aircraft involved in the accident. The airport quickly became congested with parked airplanes blocking the only taxiway and forcing departing aircraft to taxi on the runway instead. Patches of thick fog were drifting across the airfield; hence visibility was greatly reduced for pilots and the control tower.

Immediately after lining up with the runway, the KLM pilot advanced the throttles and the aircraft started to move forward. The co-pilot advised the captain that ATC clearance had not yet been given, and Captain Veldhuyzen van Zanten responded, ?I know that. Go ahead, ask.? Meurs then radioed the tower that they were ?ready for takeoff? and ?waiting for our ATC clearance.? The KLM crew then received instructions which specified the route that the aircraft was to follow after takeoff. The instructions used the word ?takeoff,? but did not include an explicit statement that they were cleared for takeoff.

Meurs read the flight clearance back to the controller, completing the readback with the statement: ?We are now at takeoff.? Captain Veldhuyzen van Zanten interrupted the co-pilot?s read-back with the comment, ?We?re going.?

The controller, who could not see the runway due to the fog, initially responded with ?OK? (terminology which is nonstandard), which reinforced the KLM captain?s misinterpretation that they had takeoff clearance. The controller?s response of ?OK? to the co-pilot?s nonstandard statement that they were ?now at takeoff? was likely due to his misinterpretation that they were in takeoff position and ready to begin the roll when takeoff clearance was received, but not in the process of taking off. The controller then immediately added ?stand by for takeoff, I will call you,? indicating that he had not intended the clearance to be interpreted as a takeoff clearance.

A simultaneous radio call from the Pan Am crew caused mutual interference on the radio frequency, which was audible in the KLM cockpit as a three-second-long whistling sound (or heterodyne). This caused the KLM crew to miss the crucial latter portion of the tower?s response. The Pan Am crew?s transmission was ?We?re still taxiing down the runway, the Clipper 1736!? This message was also blocked by the interference and inaudible to the KLM crew. Either message, if heard in the KLM cockpit, would have alerted the crew to the situation and given them time to abort the takeoff attempt.

Due to the fog, neither crew was able to see the other plane on the runway ahead of them. In addition, neither of the aircraft could be seen from the control tower, and the airport was not equipped with ground radar.

After the KLM plane had started its takeoff roll, the tower instructed the Pan Am crew to ?report when runway clear.? The Pan Am crew replied: ?OK, we?ll report when we?re clear.? On hearing this, the KLM flight engineer expressed his concern about the Pan Am not being clear of the runway by asking the pilots in his own cockpit, ?Is he not clear, that Pan American?? Veldhuyzen van Zanten emphatically replied ?Oh, yes!? and continued with the takeoff.

Moments later, the Pan Am crew spotted the KLM?s landing lights through the fog. When it became clear that the KLM was approaching at takeoff speed, Grubbs exclaimed, ?Goddamn, that son-of-a-bitch is coming straight at us!? while the co-pilot Robert Bragg yelled, ?Get off! Get off! Get off!?. The Pan Am crew applied full power to the throttles and took a sharp left turn towards the grass in an attempt to avoid a collision. By the time the KLM pilots saw the Pan Am, they were already traveling too fast to stop. In desperation the pilots prematurely rotated the aircraft and attempted to clear the Pan Am by climbing away. The KLM was within 330 ft of the Pan Am when it left the ground. Its nose gear cleared the Pan Am, but the engines, lower fuselage and main landing gear struck the upper right side of the Pan Am?s fuselage at approximately 140 knots.

Both airplanes were destroyed. All 234 passengers and 14 crew members in the KLM plane died, as did 326 passengers and nine crew members aboard the Pan Am, primarily due to the fire and explosions resulting from the fuel spilled and ignited in the impact. The other 54 passengers and seven crew members aboard the Pan Am aircraft survived, including the captain, first officer and flight engineer.

The subsequent investigation by Spanish authorities concluded that the primary cause of the accident was the KLM captain?s decision to take off in the mistaken belief that a takeoff clearance from air traffic control (ATC) had been issued. Dutch investigators placed a greater emphasis on a mutual misunderstanding in radio communications between the KLM crew and ATC, but ultimately KLM admitted that their crew was responsible for the accident and the airline agreed to financially compensate the relatives of all of the victims.

The disaster had a lasting influence on the industry, highlighting in particular the vital importance of using standardized phraseology in radio communications. Cockpit procedures were also reviewed, contributing to the establishment of crew resource management as a fundamental part of airline pilots? training.

Attachments

The close of the 1930s had brought with it the start of World War II. It had a profound impact on fashion in the first half of the 1940s, and even after the war had ended.

Fashion during the war was dominated by rationing. Utility clothing and uniforms were the most ubiquitous forms of ?fashion? during the war. Squared shoulders, narrow hips, and skirts that ended just below the knee were the height of fashion. Tailored suits were also quite popular.

However, there were also many girls who showed a very cool style of dress during this period with a combination of shorts and crop tops.

Fashion during the war was dominated by rationing. Utility clothing and uniforms were the most ubiquitous forms of ?fashion? during the war. Squared shoulders, narrow hips, and skirts that ended just below the knee were the height of fashion. Tailored suits were also quite popular.

However, there were also many girls who showed a very cool style of dress during this period with a combination of shorts and crop tops.

Attachments

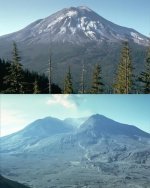

Mount St. Helens Photographed From The Same Spot, One Day Before, And Four Months After Erupting

Mount St. Helens erupted on May 18, 1980. The volcano, located in southwestern Washington, used to be a beautiful symmetrical cone about 9,600 feet (3,000 meters) above sea level. The eruption, which removed the upper 1,300 feet (396 meters) of the summit, left a horseshoe-shaped crater and a barren wasteland

Mount St. Helens erupted on May 18, 1980. The volcano, located in southwestern Washington, used to be a beautiful symmetrical cone about 9,600 feet (3,000 meters) above sea level. The eruption, which removed the upper 1,300 feet (396 meters) of the summit, left a horseshoe-shaped crater and a barren wasteland

Attachments

1956: For A Bet Whilst Drunk, Former Marine Thomas Fitzpatrick Stole A Small Plane From New Jersey And Then Landed It Perfectly On A Narrow Manhattan Street In Front Of The Bar He Had Been Drinking At

He had made a bet with a fellow drinker that he could leave the bar, go to New Jersey, and then get back in 15 minutes.

He did nearly the exact same thing two years later, after a bar patron refused to believe he had done the first one.

He had made a bet with a fellow drinker that he could leave the bar, go to New Jersey, and then get back in 15 minutes.

He did nearly the exact same thing two years later, after a bar patron refused to believe he had done the first one.